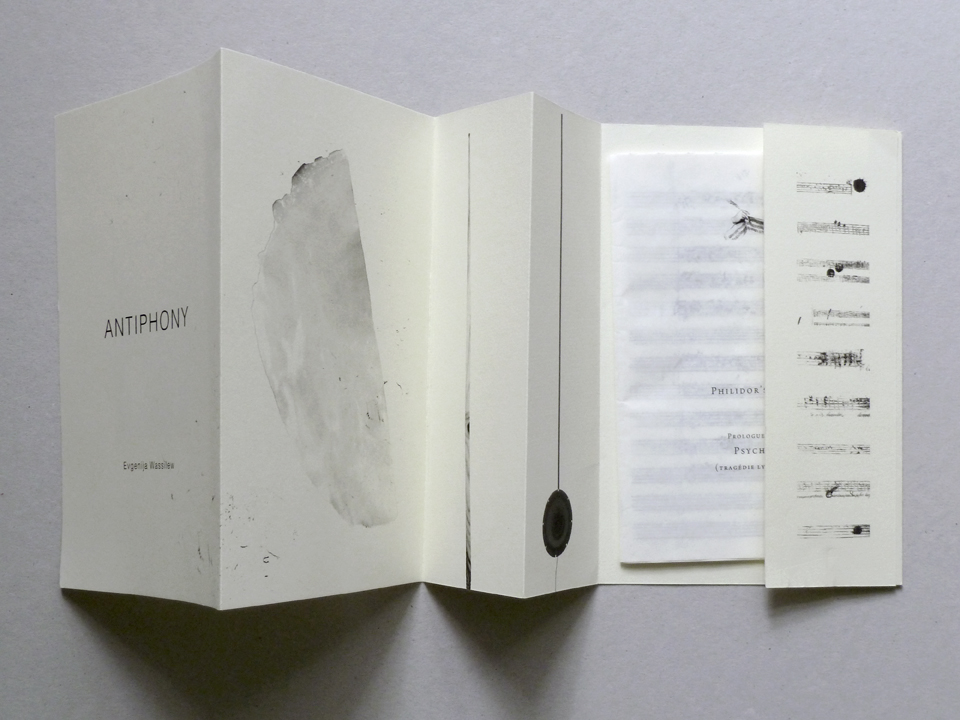

Antiphony / Philidor’s Ink, envelope 21 cm x 14-56 cm, booklet 23 pages, 18,5 cm x 13 cm, dessins imprimés sur cellulose fiber parchment paper 30g, papier 170g, 1200 ex, éditions Pollen, Association Pollen, Monflanquin 2012

Intrigued by the tragic-comic circumstances surrounding the accidental death of one of the great Baroque composers, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Evgenija Wassilew discovered in her research the existence of the „Fonds Philidor“ at the Bibliothèque de Versailles. Hand copied by Philidor L’Aisné, these scores are available today as digital images. Investigating the technique behind the production of these „copies of copies“ the artist was drawn to Psyché, an opera composed by Lully in 1687, whose evocative title intuitively echoes the origin of her project.

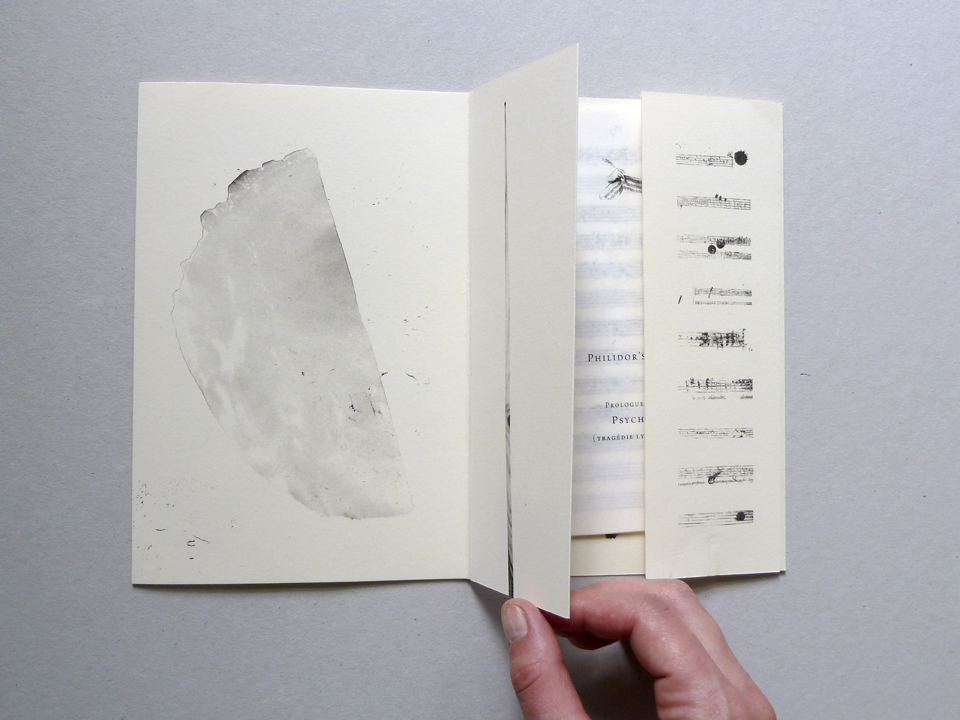

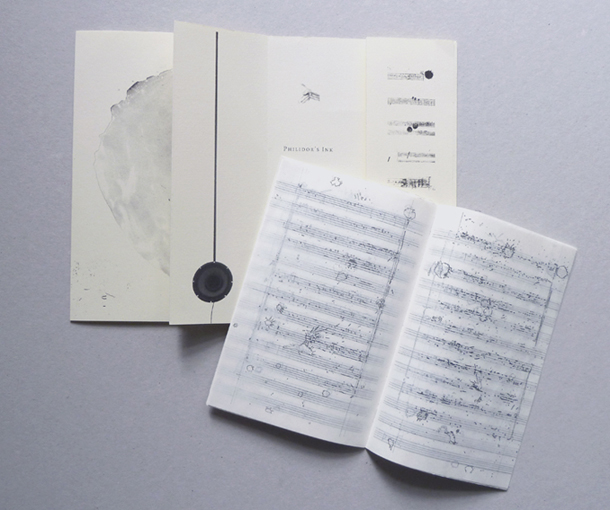

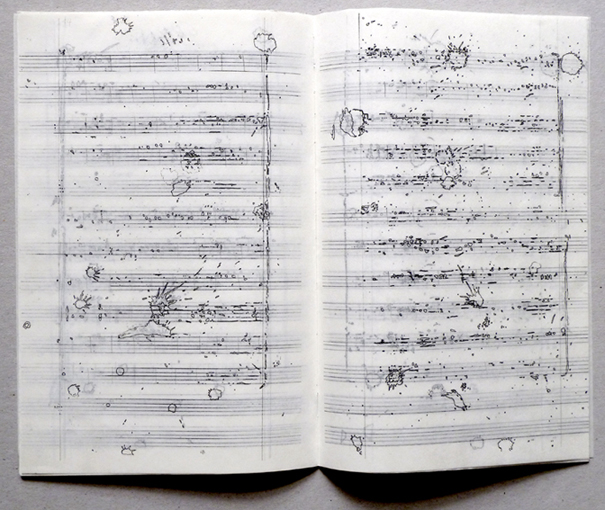

These documents are not perfect objects: upon paper made fragile by the passing of time, traces of the scribe’s work have been retained. In particular, the artist chanced here upon the accidental: drops of diluted ink, effaced errors, here and there a shadow that obscures the handwritten composition from the inside out. Typically removed in the process of digitalization (black and white contrasts are in effect augmented in order to facilitate reading), these vestiges of ink left on the scanned copies of Psyché mistakenly preserve, and thus replay, traces of the 17th century „composed by the hasty hand of the scribe and the paper’s thirst for ink.“

If Evgenija Wassilew has in the end chosen to work on this score, it is not however in order to reveal the faults of a system. Bringing these small slips and failures to light, she nourishes that side of contemporary creation marked by the de-hierarchisation of the given and the re- integration of error. From the point of view of a fundamentally fragile and „molting“ humanity, measured as much by its errors as by its ideals, these works tempt us towards imperfection. It is our „physical and psychological nature“ that we hopeless try to hide, being driven by a dream of perfection.

For the exhibition at Pollen in Monflanquin, Evgenija Wassilew articulates a scene woven around the visible and audible elements of the Prologue to Lully’s Psyché. She begins by transforming the digital source „like an x-ray“, darkening the stains and lightening the notes. She thus operates in a manner opposed to that of the „contemporary scribes“, who strip away that which obscures our reading of the original. To a certain extent she approaches these images as a scientist would a palimpsest, attempting to recover a prior gesture effaced by a more recent layer of knowledge. To render these withdrawals readable, the artist makes an imprint on tracing paper, which she mounts between two plates of glass.

The contrast between the darkening of certain elements and the lightening of others disrupts the logical perspective: are we witnessing the corruption of the score or its illumination?

From these imprints the artist recopies by hand, in the manner of the scribe, what she has made visible. Drawn on fine sheets of paper half-way between the hand-made paper of the original and the tracing paper of the imprint, these „scores of noise“ -Philidor’s Ink- pay tribute to what should not be seen, to what should not be read.

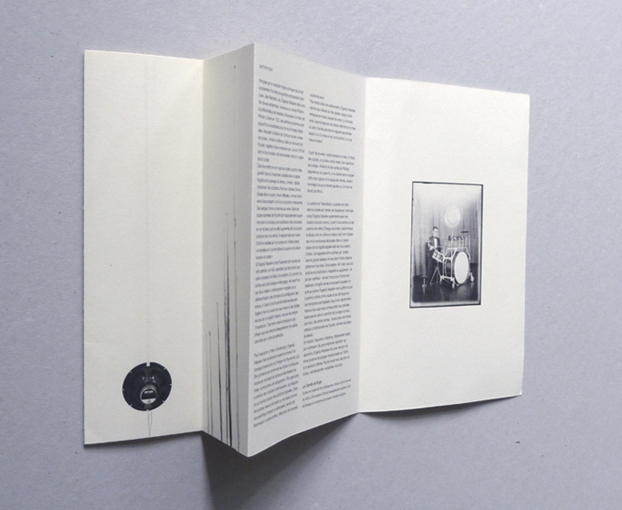

The question of interpretation raised through the artist’s rereading is doubly posed, as Wassilew further experiments with the possibility of an audible translation on the basis of a set of drums that she herself has constructed. Anachronistic and disjointed, it is a strange instrument equipped with casings 3 mm thick fiberboard and membranes of tracing paper, whose fragility recalls that of the documents of old. The drumsticks are sculpted by the artist out of great lengths of wood, the tips patiently fashioned. These handmade drums play upon imitation and duplication: appearing to be a model by the nature of the material, it has in fact been conceived in order to function, the fragility of its parts appealing to another play on sound. Evgenija Wassilew makes audible what the score obliterates, and the effect of striking the membranes weakens them to the point of rupture. Alternating sharp blows, which correspond to the larger splashes in this „score of noise“, with those more soft of the smaller stains, the artist offers a contemporary reinterpretation of Psyché punctuated by expanses of silence.

Entitling the exhibition Antiphony – translated literally as „counter-sound“, from the Greek antiphonê, meaning „who replies“ – Evgenija Wassilew allows an ancient form of musical language based on echo and differed repetition to resurge: Psyché reborn from the rivers of time, melodiously soiled, „stained“ with noise.

Antiphony / Philidor’s Ink, envelope 21 cm x 14-56 cm, booklet 23 pages, 18,5 cm x 13 cm, printed drawings on cellulose fiber parchment paper 30g, book paper 170g, 1200 ex, éditions Pollen 2012

text by Camille de Singly, english translation: Matthew Fielding

Intriguée par le caractère tragico-comique de la mort accidentelle d’un des plus grands compositeurs baroques, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Evgenija Wassilew découvre, lors de ses recherches, l’existence du «fonds Philidor» à la Bibliothèque de Versailles. Recopiées à la main par Philidor L’Aisné, ces partitions anciennes sont aujourd’hui consultables sous forme d’images digitalisées. Analysant la facture de l’écriture de ces «copies de copies», l’artiste s’arrête sur celle du manuscrit de Psyché, tragédie lyrique composée par Lully en 1678 et dont le titre évocateur fait intuitivement écho à l’origine de son projet. Ces documents ne sont pas des objets parfaits: elles gardent trace du travail des copistes dans le papier fragilisé par le passage du temps. Wassilew y décèle notamment des accidents d’écriture: taches d’encre diluées dans le papier, erreurs effacées, ombres recto-verso obscurcissant ici et là la composition manuscrite. Ces vestiges d’encre préservés par erreur dans les copies scannées de Psyché sont habituellement supprimés dans le processus de numérisation (les contrastes en noir et blanc sont en effet augmentés afin de faciliter la lecture des documents). Ils rejouent ainsi les traces d’écriture laissées par les copistes du XVIème siècle, «composée par la plume hâtive du copiste et la nature buveuse du papier.»

Si Evgenija Wassilew choisit finalement de travailler sur cette partition, ce n’est cependant pas tant parce que celle-ci révélerait les failles d’un système. En portant à la lumière les ratages et dérapages, elle nourrit ce pan de la création contemporaine marquée par la déhiérarchisation des données et la réintégration des erreurs. À l’aune d’une humanité fondamentalement fragile et mue tout autant par ses erreurs et ses faiblesses que par un objectif d’absolu, ces œuvres tentent l’imperfection. C’est notre «nature physique et psychique» que nous tentons désespérément de cacher, obnubilés par un rêve de perfection.

Pour l’exposition à Pollen à Monflanquin, Wassilew tisse les éléments visuels et sonores d’un paysage articulé autour du Prologue de Psyché de Lully. Elle commence par transformer les fichiers numériques sources en noircissant les taches et blanchissant les notes, «comme dans une radiographie». Elle opère ainsi a contrario des «copistes contemporains», qui élaguent ce qui brouille la lecture des partitions originelles. Dans une certaine mesure, elle revient sur les scans comme une scientifique traiterait un palimpseste, tentant de faire resurgir un geste antérieur, effacé par une nouvelle couche de savoir. Pour rendre lisible ces prélèvements, Evgenija Wassilew imprime leurs relevés sur des papiers calque qu’elle entrepose entre deux plaques de verre. Le contraste entre l’assombrissement de certains éléments et la mise au blanc d’autres perturbe les logiques perceptives: assiste-t-on à la mise au noir de la partition, ou à sa mise en lumière?

À partir de ce relevé, l’artiste recopie à la main, à l’instar des copistes, ce qu’elle a rendu visible. Ces « partitions de bruitage » Philidor’s Ink (les taches de Philidor), dessinées sur du papier fin, à mi-chemin entre le papier chiffon des originaux et le calque des relevés, rendent hommage à ce qui ne devrait pas être vu, à ce qui ne devrait pas être lu.

La question de l’interprétation, soulevée par cette relecture opérée par l’artiste, est doublement interrogée puisqu’Evgenija Wassilew expérimente aussi une possible traduction sonore, à partir d’une batterie qu’elle construit elle-même. Etrange instrument, anachronique et décalé, doté de coffres en médium de 3 mm d’épaisseur et de membranes découpées dans un papier calque dont la fragilité rappelle celle des documents d’antan. Les baguettes sont sculptées par l’artiste dans de grands tasseaux en bois dont l’artiste dessine patiemment les olives. Cette batterie «fait-main» joue sur le factice et la duplication: maquette en apparence – de par ses matériaux – elle est conçue pour fonctionner réellement, la fragilité de ses composants appelant un autre jeu sonore. Evgenija Wassilew rend audible ce que la partition oblitère, et les traces du jeu de frappe sur ces membranes les fragilisent jusqu’à leur déchirement. Alternant les coups secs correspondant aux grandes éclaboussures dans la «partition de bruitage» et ceux, plus doux, des petites taches, l’artiste pose une réinterprétation contemporaine de Psyché, rythmée de plages de silence.

En intitulant l’exposition Antiphony, littéralement traduit par «contreson» (du grec antiphonê, signifiant «qui répond à»), Evgenija Wassilew fait aussi resurgir une forme ancienne de langage musical basée sur l’écho et la répétition différée. Psyché renaît ainsi des flots du temps, mélodieusement «entachée» de bruits.